Attributes of melody include its compass, that is, whether it spans a wide or narrow range of pitches, and whether its movement is predominantly conjunct (moving by step and therefore smooth in contour) or disjunct (leaping to non-adjunct tones and therefore jagged in contour). Conversely, music may employ pitch material but not have a melody, as is the case with some percussion music. Melody can be synonymous with tune, but the melodic dimension of music also encompasses configurations of tones that may not be singable or particularly tuneful.

#ELEMENTS OF MUSIC PLUS#

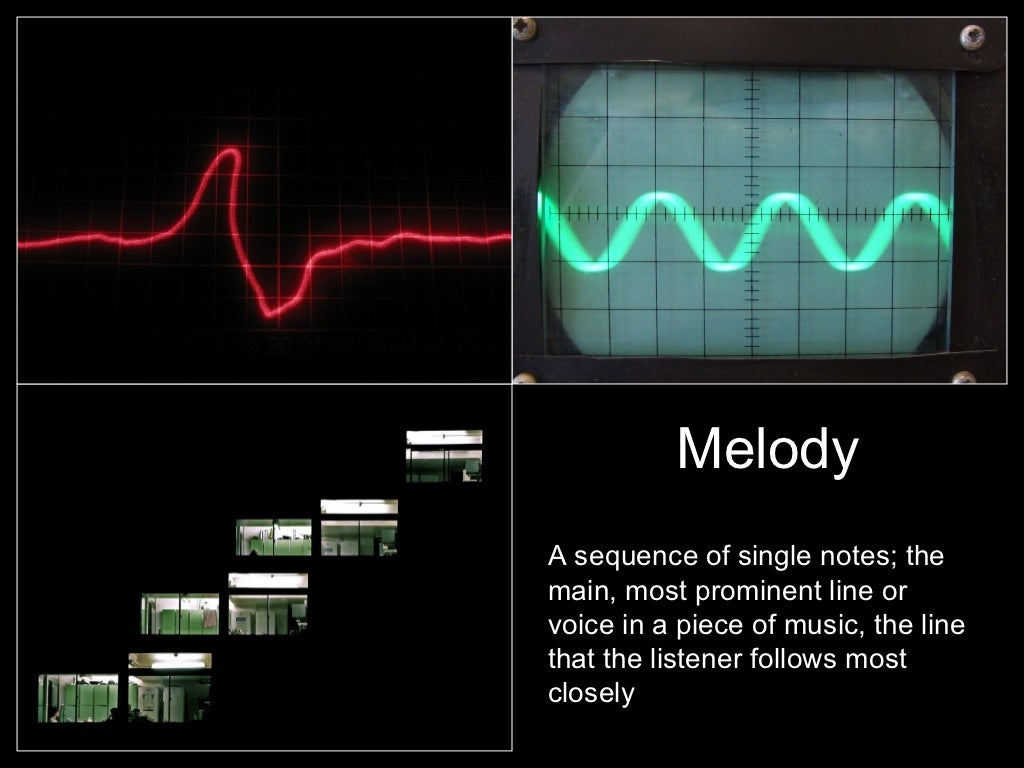

A musical tone has two fundamental qualities, pitch and duration, and both of these enter into the succession of pitch plus duration that constitutes a melody. By its very nature, melody cannot be separated from rhythm. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is in C minor because its basic musical materials are drawn from the minor scale that starts on the pitch C.Ī succession of musical tones perceived as constituting a meaningful whole is called a melody. Key is the combination of tonic and scale type.

Most melodies end on the tonic of their scale, which functions as a point of rest, the pitch to which the others ultimately gravitate in the unfolding of a melody. The starting pitch of a scale is called the tonic or keynote. Another important scale type particularly associated with music from China, Japan, Korea, and other Asian cultures is pentatonic, a five-note scale comprised of three whole steps and two intervals of a step and a half. Major and minor are two commonly encountered modes, but others are used in folk music, in Western European music before 1700, and in jazz.

The position of the whole and half steps in the ascending ladder of tones determines the mode of the scale. Most Western European music is based on diatonic scales-seventone scales comprised of five “whole steps” (moderate-size intervals) and two “half steps” (small intervals). Each element of a scale is called a “step” and the distance between steps is called an interval. The conventional approach to classifying pitch material is to construct a scale, an arrangement of the pitch material of a piece of music in order from low to high (and sometimes from high to low as well). And just as the Fahrenheit and Celsius systems use different sized increments to measure temperature, different musical cultures have evolved distinctive pitch systems. All theoretical systems of music organize this pitch continuum into successions of discrete steps analogous to theĭegrees on a thermometer. Pitch, like temperature, is a sliding scale of infinite gradations. The alto saxophone is smaller and has a higher range than the slightly larger tenor saxophone. The longest wooden bars of a xylophone produce the lowest pitches, the shortest produce the highest. The same principle is visible in the construction of many instruments. Thus, men’s voices are usually lower than those of women and children, who have comparatively shorter and thinner vocal cords. In general, longer and thicker objects vibrate more slowly and produce lower pitches than shorter and thinner ones. Frequency is determined by the length and thickness of the vibrating object. As we have seen, in terms of the physics of sound, pitch is determined by frequency, or the number of vibrations per second: the faster a sounding object vibrates, the higher its pitch.Īlthough the audible range of frequencies for human beings is from about 20 to under 20,000 vibrations per second, the upper range of musical pitches is only around 1,000 vibrations per second.

Pitch refers to the location of a musical sound in terms of low or high. A distinctive sequence of longs and shorts that recurs throughout an individual work or groups of works, such as particular dance types, is called a rhythmic pattern, rhythmic figure, or rhythmic motive.

The first beat of each metric group is often described as accented to characterize its defining function in the rhythmic flow ( My country ‘tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing-six groups of three beats, each beginning with the underlined syllable).Īnother important rhythmic phenomenon is syncopation, which signifies irregular or unexpected stresses in the rhythmic flow (for example, straw- ber-ry instead of straw-ber-ry). Recurrent groupings of beats by two’s, three’s, or some combination of two’s and three’s, produces meter.

#ELEMENTS OF MUSIC FREE#

Soliloquy)-what is called nonmetered or free rhythm-or may occur so as to create an underlying pulse or beat (“bubble, bubble, toil and trouble”-four beats coinciding with buh–buh–toil–truh-from the witches’ incantation in Macbeth ). The succession of attacks and durations that produces rhythm may proceed in a quite unpredictable flow (“to be or not to be, that is the question”-the opening of Hamlet’s

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)